|

Observation of Village Elections in Fujian and the Conference to Revise The The Carter Center would like to acknowledge the generous support of the Starr Foundation, the AT&T Foundation, the Ford Foundation, the United States-China Business Council, the Chase Manhattan Foundation, and the Loren W. Hersey Family Foundation. Their financial support has enabled us to work with both the Ministry of Civil Affairs and the National People’s Congress on Chinese local elections. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Table of Contents |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

At the invitation of the Ministry of Civil Affairs (MCA), a group of Carter Center observers visited Dehua and Xianyou counties in Fujian Province from August 1 through 5, 2000. The observers, including scholars from Duke University and two Western journalists, visited one village in Dehua where a “big sea-election” was held and observed elections in two other villages in Xianyou. Fujian is one of the first provinces to have elections observed by Westerners. The International Republican Institute observed village elections in Fujian in 1994. Fujian is also one of the four Chinese provinces that were selected to participate in the MCA-Carter Center Project to Standardize Procedures of Villager Committee (VC) Elections. The Center first observed village elections in Fujian in 1997, after which it published its first report on China’s elections. In the summer of 1998, the Center again visited Fujian and collected village election data from three counties (districts) in Fujian: Xianyou, Gutian and Huli District in Xiamen City. CNN, through a 30-minute documentary on village elections in Fujian, introduced China’s village elections to its viewers in 1998. Earlier observations by the Center staff and other Westerners provide us with a comparative perspective and make it possible for us to identify changes in Fujian’s village elections. It is the Center’s belief that the provincial leaders in Fujian, particularly those at the Provincial Department of Civil Affairs, are exceptionally good in learning from the experience of the past village elections and forward looking in introducing procedures that can drastically improve the quality of these elections. They have been working hard to train election officials at all levels and carry out civic education in a very effective manner in the countryside. They are open-minded and have discussed with us the problems in these elections without any reservation. The three elections The Carter Center delegation observed in August 2000 were all conducted according to the old Fujian Provincial Measures on Village Elections, which were revised twice to keep pace with changing practices. There were clearly huge efforts on the part of the election officials at all levels to introduce more openness, competition and participation in the process. We were impressed by the efforts to make these elections more competitive, the strict application of the principle of ballot secrecy, open count and immediate announcement of the election result, and the good work in conducting these elections in a relatively professional manner. Following our observation of the elections in Fujian, members of the delegation attended a conference in Beijing on August 6 and 7 to revise The National Procedures on Village Elections (hereafter the National Procedures) organized and sponsored by the MCA and The Carter Center. A total of fifty-five people attended the conference. Officials from various central and local government agencies in Beijing and seven provinces, as well as leading scholars from both Chinese and Hong Kong academic institutions, were present at the conference. The discussions at the conference were lively, candid and focused, touching on all issues related to the improvement of village elections in China. All suggestions and recommendations will be incorporated into the revised National Procedures to be published in 2001. This report is divided into two parts. The first part focuses on the Fujian observations. It briefly reviews the past observations of Fujian’s village elections and the data collected from Fujian in 1998. It will then introduce the new changes in Fujian’s Provincial Measures on Village Elections that were adopted by the Standing Committee of the Fujian People’s Congress on July 28, 2000 and report some of the exchanges and activities during our observation. A detailed report of the procedures of the three elections will follow. Following that, we will, as we have done in the past, identify what we think are areas of weakness and deficiency and offer recommendations on how they can be improved. In the second part of the report, we highlight the heated discussions at the conference on the problems of village elections and how participants suggested these difficulties could be overcome. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Background on Fujian and Its Village Elections With a population of 31 million and 17 million registered rural voters, Fujian has 83 counties, 971 townships, and 14,801 villages.(1) Fujian was one of a few provinces in China that began village elections before the Provisional Organic Law on Villager Committees (hereafter the Organic Law) was adopted by the National People’s Congress (NPC) in November 1987 and mandated these elections. Elections of villager committees were conducted in Fujian first in 1984 and 1987. There were no uniform procedures in these two elections. In 1989 direct election of villager committees was urged by the Provincial Department of Civil Affairs on a trial basis throughout the province. Three more rounds of village elections were conducted in 1991, 1994 and 1997, respectively. Fujian was also the first province in China to promulgate provincial implementation measures under the Organic Law on the Villager Committee and provincial village election measures were revised in 1988 and 1990 respectively.(2) Officials in Fujian made progress through trial and error, learning from foreign observers of their elections and observing elections in foreign countries. For example, in the first two rounds of villager committee elections, candidates were chosen through indirect means or by outright appointment, and villagers voted only on committee members, and the elected members then nominated their chairs and vice chairs. By the next round of elections in 1991, all positions were directly elected, multiple candidates were mandatory for each and every position and voters could freely associate and nominate candidates. In September 1993, the Fujian People’s Congress amended the Provincial Measures for Villager Committee Elections, stipulating the principle of one-person, one-vote and dropping the previous system of one-household, one-vote.(3) In 1989, only 38 percent of the villages completed elections; in 1997, 99.67 percent completed them. Fewer than 9 percent had primaries in 1989 while 77 percent had them in 1997. Most significantly, none of the elections in 1989 used a secret ballot, but 95 percent used it in 1997.(4) Fujian led the nation in promoting the system of villager representative assemblies (VRA) and the open administration of village affairs. By 1998, 96 percent of the villages in Fujian had VRAs, and most of the villages set up public bulletin boards for villagers to view village’s official transactions such as revenue and expenditure audits, homestead assignment, family planning implementation, electricity charges and other matters.(5) During The Carter Center’s 1998 observation, Zhang Xiaogan, chief of the Basic-level Governance Section in Fujian’s Department of Civil Affairs, told us that he began to promote the idea of polling stations in Fujian after his visit to the United States.(6) Through more than a decade of promoting village elections, Fujian officials began to implement a series of measures that were designed to improve the quality of the village elections and increase their competitiveness and meaningfulness. These measures, many of which were borrowed and implemented by other provinces, as of August 2000 include:

In addition, other methods designed to combat clan influence and organizational manipulation and to increase transparency were introduced. For example, the idea that candidates could pick their own poll monitors was quite popular. As a result, peasants in Fujian began to participate in these elections on their own volition on an unprecedented scale and were highly alert to possible violation of the electoral measures. During the term election in 1997, more than 4,000 letters of complaint about election irregularities were sent by farmers to various levels of the Fujian government, ten times the number in 1993.(8) |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Fujian Village Elections as Observed by Westerners In its observation of the villager committee election in Fujian in 1994, the International Republican Institute (IRI) noted “some striking differences in how election procedures were carried out in different parts of the province” and concluded that elections in the more rural settings were conducted far better and fairer than the elections in the more urbanized areas. The IRI called for “a more standardized and consistent electoral processes throughout the province.” IRI’s recommendations included, among others, standardized comprehensive civic education at the county, if not the province, level, a clearer definition of the responsibilities of the election leadership committees to ensure openness and transparency in the electoral procedures, the introduction of a direct primary to determine final candidates, the use of one single ballot to elect all members of the villager committee, making popularity as the sole criteria for candidates’ eligibility, the development of a strict set of rules for campaigning, the adoption of a standardized and simplified polling process, enhancement of ballot secrecy and the reduction of the use of proxies and roving ballot boxes.(9) In 1997 the IRI returned to Fujian and observed a new round of villager committee elections. IRI observers noted many significant changes in electoral practices implemented by the provincial government, which included (1) mandatory use of secret ballots and ballot booths or private voting rooms in all elections; (2) mandatory review of primary candidates by township and village election committees to ensure they are qualified to hold office; (3) optional use of polling stations to provide villagers with more convenient voting venues; (4) elimination of proxy voting during elections; (5) mandatory audits of the income and expenditures of incumbent village committees and public display of the audits; and, (6) permission for candidates to appoint monitors to oversee voting at polling stations.(10) In its observation report, the IRI praised the electoral administration in Fujian as “unquestionably sound” and its electoral system as “effective and comprehensive.” In its view, the Fujian electoral regulations were “clear” and the election workers were “trained and knowledgeable.” However, IRI did identify technical deficiencies and repeated some of the recommendations that had been made three years ago. New recommendations focused primarily on improving the quality of electoral administration. A few of these suggestions were very noteworthy. IRI recommended that the so-called “drop-down” election system (In which the votes earned by a losing candidate for a higher position be added for those received for a lower position) be removed and that there be two formal candidates competing for each open villager committee seat. It advised that a public forum be provided for voters to hear candidate speeches and to ask questions. It also called for formal and informal occasions for county election officials to share election experience and to exchange information on voting procedures and civic education activities.(11) In April 1997, CNN taped two village elections in Fujian and broadcast the story entitled “Bamboo Ballot Box” to a worldwide audience in July. Andrea Mitchell praised the two elections as “fair, democratic and true,” an improvement as compared to elections a few years ago in which voters simply raised their hands to endorse candidates. The Carter Center began its work on China village elections in 1997. Its first official observation took place in Fujian’s Gutian County. While the Center observers cautioned against generalizing from the small number of cases, they concluded that “China’s village elections are a significant and positive development in empowering China’s 900 million farmers.” They observed that the village elections they saw “demonstrate a remarkably high level of technical proficiency,” and that the elections, according to many of the people they met, “have improved the lives of the villagers in many ways” because the leaders were more accountable. They suggested that MCA officials “should consider concentrating on two tasks in the next stage: a) ensuring a higher degree of standardization within counties and perhaps within provinces, and b) lifting the levels of electoral expertise for villagers to that of the best villages that we saw.”(12) Of the two villages the Center delegation observed, competition in one village was quite lively. The incumbent chair, who was running for a third term, lost to an electrician three years his senior who promised to lead the poorer villagers to become rich as soon as possible. One of the candidates for the villager committee, who had lost the previous election by a single vote, had spent three years campaigning to win the villagers’ trust and support. He received the highest number of votes in the primary but came in second in the final election. In fact, none of the candidates won enough votes to serve as a member of the villager committee. That would be decided by a run-off.(13) The Center observers made a fourteen-point list of recommendation to the MCA, which were warmly received by the MCA and provincial officials. Some of these recommendations included improvement of civic education programs, standardization of electoral procedures, synchronization of election dates in the county or province, better nomination methods, enforcement of election law, implementation of the principle of secret ballot and more in-depth research of procedures and consequences of village elections.(14) In March 1998, the Carter Center signed a Memorandum of Understanding with the MCA and visited Fujian in late June to install three computers in three pilot counties. The Center delegation went to Xianyou County in Quanzhou and Huli District in Xiamen. It did not observe any elections but looked at the village election data at the county (district) office and talked with election officials at all levels. A group of the Center delegates witnessed an interesting exchange between the provincial chief of basic-level governance and Huli district election officials. The former did not approve the so-called “drop-down” method whereby the loser of the vote for the chair could have a second or third try as vice chair or committee member. He thought that was just a way to allow a small clique in the township to run the entire village and that the practice of this method in Huli had clouded the overall picture of Fujian’s village elections. In addition to denouncing the election monitoring as useless and unnecessary, District officials warned the director that the one-candidate one-chance method (as opposed to the drop-down method) would eventually deplete the villages of those who were willing and had the capability to serve.(15) |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Electoral Data of the Three Pilot Counties (District) in Fujian In late 1998 and early 1999, three counties (districts) in Fujian reported the election data of 1997 to the MCA office in Beijing through the Village Election Data-gathering System designed jointly by the MCA and The Carter Center. Gutian County is located in north central Fujian, close to the provincial capital Fuzhou. This county has 15 townships with 207 villages. Since 1984 six rounds of elections have been conducted, in 1984, 1987, 1989, 1991, 1994 and 1997, respectively. According to the standards set by the provincial government, 97 percent of the villager committees were operational, with 65 percent doing very well. Gutian has been named a national model county twice, in 1995 and 1999. Huli District of Xiamen City is located in north Xiamen Island, and was established in October 1987. It has one township and one district with 11 villager committees, 22 urban neighborhood committees, and 39,000 farmers. The annual industrial output in 1996 was RMB 2.48 billion with more than 100 million in revenue. The average per capita income is RMB 4,500. It has held 6 rounds of elections and became a model county in 1999. Xianyou County is in south-central Fujian with 19 townships and 304 villages. The first election, as a provincial pilot county, was held in 1990, and 99 percent of the villager committees met the provincial standards. In 1994, 90 percent of the villages participated in the second round of demonstration elections. Xianyou was selected twice as the provincial model county for village elections, and became a national model county in 1999. The basic information on the three counties is as follows: Table I: Fujian

One important component of village elections that the Center and the MCA are looking into carefully is the formation of the election leadership committee (ELC). How members of the ELC are selected and how many of them are Party members will shed significant light on the availability of choice and competitiveness of the village election. The data shows that in the three Fujian counties more than 95 percent of the ELC members were selected by voters in various manners and about 45 percent of the ELC members are Party members. Since the Organic Law did not stipulate how to nominate candidates in village elections, it was up to provinces to self-regulate.(16) The nomination method stipulated by Fujian, which permitted only five voters freely associated to make nominations, was considered by the MCA as too limited and did not give voters as much choice as the so-called haixuan (“sea-election”), a method method invented by villagers in Lishu County, Jilin Province, which allows all eligible voters to nominate candidates.(17) In determining final candidates, 97.26 percent of the villages in Fujian counties (districts) used the method having the VRA select them, a limited primary attended usually by less than 10 percent of the villagers that are in various influential positions in a village.(18) Although Fujian did not introduce the more advanced haixuan nomination, it led Hunan and Jilin provinces in fielding multiple candidates for the chair during the election for which data was collected during the pilot phase of the Center’s Project. The 1998 survey of the 3,267 villages in the three provinces indicated that there was only one candidate for the chair in 1,664 villages, accounting for 49.07 percent of all the villages. However, in Fujian, only 16.41 percent of the villages had a single candidate for the chair, a percentage significantly lower than the other two provinces (61.06 percent in Hunan and 51.68 percent in Jilin).(19) Fujian’s strength was also reflected in the small number of proxy votes during the 1997 village election. It is well known that the use of proxies often compromises the principle of ballot secrecy and creates easy opportunities for clan influences and township and village leaders to manipulate the electoral procedure. The following table on the use of proxies illustrates the restricted use of proxies in all three Fujian counties as compared to Hunan and Jilin. Table II: Fujian

As the MCA indicated in its project report, proxy voting and roving ballot boxes used to prevail in village elections, and it was quite common for fathers to vote for their children and husbands for their wives. Although the original purpose to allow proxy voting and to use roving boxes is to provide convenience to the ill and the elderly, villages began to use them to replace the election meeting. Fujian worked hard to restrict proxy voting, but there were still many villagers who cast their ballots into the roving boxes as indicated by the data collected from nine counties in the three provinces studied (see Table III). Table III

At the pilot stage of the Center’s project in China, we tried to assess the competitiveness of village elections through checking the percentage of votes received by the winning candidates. If a candidate wins with over 2/3 of the ballots, the election is not very competitive; if a candidate wins with less than 2/3 of the ballots, the election is relatively competitive. The data from the nine counties show that 2,969 out of the 3,267 villages successfully elected their village chairmen. 1,709 chairs got more than 2/3 of the vote, which accounts for 57.56% of all the elected chairs, and 1,206 elected chairs got less than 2/3 votes, accounting for 42.44%. Fujian’s three counties do not appear to be different from the other six counties (see Table IV). Table IV

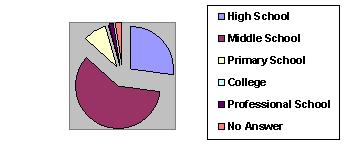

The joint survey also collects data on the age, education, gender and political affiliation of elected villager committee chairs. These data can demostrate demographic changes that are engendered by this new system of choice and accountability. Data from the three counties in Fujian seems to suggest that, like the other six counties, voters were able to pick younger (see Table V) and better educated (see Table VII) villagers to be their leaders. The data also shows that membership in the Communist Party and incumbency were very relevant and that women were very much less likely to be elected VC chairs (see Table VI). Table IV

Table VI

Table VII

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Fujian’s Amended Provincial Election Measures The original Fujian Province Villager Committee Electoral Measures (Measures) were promulgated in 1990 after many years of debate, following adoption in 1988 of provincial measures implementing the 1987 Organic Law on Villager Committees. These measures played an important role in promoting village self-government in Fujian. The 1988 Fujian Province Implementing Measures and 1990 Election Measures were both revised in 1993 and again in 1996. After adoption by the National People’s Congress of the permanent Organic Law in 1998, Fujian immediately began work on revising its implementing and electoral measures. Due to controversy over several issues, these measures were not adopted until July 28, 2000. Fujian officials informed us that it took two years of deliberation at the Standing Committee of the Provincial People’s Congress for the Measures to be adopted. After the first reading, the Standing Committee ordered a survey of 100 villages to see what the villagers thought of the provisions. After a re-draft, the Measures went through two more readings. Issues of importance in the Measures include specifying the right to withdraw from candidacy, provision for primaries to be handled in three different ways (through Villager Small Groups (VSG), the Villager Representative Assembly (VRA) or the Villager Assembly (VA), the abolition of proxies and other provisions to reduce election costs. In a province with over 10,000 villages, a certain measure of flexibility is very important. Mr. Zhang Xiaogan, Fujian’s point man in running village elections, also noted that one of the significant changes incorporated into the amended Measures, at the insistence of him and his colleagues, is the elimination of any language about candidates’ eligibility requirements and endorsement of candidates by officials at the township level. “Villagers,” said Zhang, “should be allowed to elect who they want regardless of background.” Highlights of the recent amendments to the Measures include:

The somewhat drastic revisions introduced by the Fujian Department of Civil Affairs and the difficulties in getting the Standing Committee of the Fujian Provincial People's Congress to approve the amendments reflected a different priority and mind-set between the two sections of the government. Civil Affairs officials desire to have a better law, easy to execute and ensuring a competitive and fair election. People's Congress leaders choose to emphasize stability and an old sense of democratic participation such as high turnout rate. The Department of Civil Affairs could not move forward with the next scheduled province-wide elections--the first round of VC elections under the 1998 permanent Organic Laws--without receiving the final approval of the Measures but it could not wait forever without doing anything, either. A passive waiting would make it much more difficult to conduct the elections on time. From early May through late July 2000, the Department began to train elections officials and pilot villages were identified to conduct elections with supervision from the provincial government and observation by county and municipal officials. These pilot elections were conducted according to the old Measures although from time to time provincial officials would ask local officials to adhere to the spirit, if not the letter, of the new Measures. The three elections we observed belonged to the trial category. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Observing Village Elections in Dehua and Xianyou Counties Qiuban Village VC Election, August 2, 2000 Following a briefing by Dehua County Party and government officials on August 1 in Dehua City, we traveled to Qiuban Village the morning of August 2 to observe one of Fujian province's first "sea elections" (or haixuan).(21) Qiuban Village is in Xiaokou Town, Dehua County. Dehua County has a population of approximately 300,000 people. Rice was being planted by hand, as we wound our way by minivan through the hills to Qiuban. Nestled among lush hillsides dotted with two-story red brick houses and temples topped with gracefully arching dragon roofs, Qiuban has 660 residents in 160 households (hu), of which 444 are registered voters. The village is divided into three VSGs. Voters living outside the county (waichu) number 80. Rice and sweet potatoes are the main crops, and there is no collective enterprise in Qiuban. Agriculture is the main occupation but cannot bring in much income. 15 percent of village revenue comes from wood processing by village carpenters. The average annual income in Qiuban is over 3,000 yuan ($340). It is a poor village. There is only one road into and out of the village, and it is 8 kilometers in either direction to the nearest village. In a village of this size, we were told the VC chair would spend an average of 10 days per month on VC work, although in larger villages of more than 10,000 this position would become full-time. The VC members receive a fixed subsidy with a bonus based on additional work during the month. The VC office is located in the school building. Posters setting forth the Organic Law (printed and distributed with sponsorship from the Center), duties of the VC, VSGs, VA and VRA in cartoon fashion, and the Village Charter were posted on the walls of the VC office. An emergency medical station was set up in the village office to treat possibly ill voters.(22) In accordance with a provincial policy introduced this year at the village level, Qiuban held a two-ballot election for the Party secretary on May 26 through household representatives. Qiuban has 12 Party members, of which four stood as candidates for secretary. For this vote, some 151 out of 153 representatives participated in casting a confidence ballot (xinren piao) for the candidates they preferred. Only those candidates who received a more than 50 percent approval rating in the confidence vote could then participate in the official election among the Party members. Mr. Wang Zeming was elected Qiuban Party Secretary. He was the chair of the "Villager Election Committee" (VEC) in Qiuban.(23) The prior VC election in Qiuban was held on April 18, 1997. Villagers clearly had problems with the incumbent VC members and did not like the way candidates were selected in the last election. With support from the township and provincial government, Qiuban requested permission to conduct an expanded sea-election (haixuan) whose procedures were as follows:(24) 1. Preparation: The prior Villager Committee (VC) convened a meeting of the VSGs to seek advice on the forthcoming seventh round of VC elections. The residents indicated they wanted to try the haixuan method this time and showed great interest in the election, even requesting to be an experimental village for this round of elections.(25) A financial audit of the VC was performed, with the results published on the village bulletin board on May 25, 2000.(26) An expanded meeting with villager representatives and others to discuss the forthcoming election and adopt an election plan (jihua) was held on June 21. The meeting also selected (tuixuan) 25 new villager representatives to form the VRA and asked the VSGs similarly to select new heads. By June 30, the new VSG heads, 25 Villager Representatives and the makeup of the Village Election Committee (VEC) was confirmed.(27) As required by the Fujian Electoral Measures, the VA, the VRA, or the VSG can form a VEC through selection. In Qiuban, the VEC was selected (tuixuan) by the VRA in a two-ballot vote on July 1. The head, Mr. Wang Zeming, was the Party secretary, and a representative from each VSG as well as representatives from the VRA completed the committee. The VRA also adopted the election regulations (guicheng), established VC member criteria, and set the registration deadline. 2. Voter Registration: Voter registration was held from July 1-4. The VEC had its first meeting on July 6, confirming that 80 voters lived away and published an updated voter registration list, including the 80 absentees, in a list posted on the village bulletin board. Voters were given until July 23 to raise any objections or comments on the voter registration list. The VEC also decided to hold its second meeting on July 20. 3. Nominations: Letters, including proxy forms, announcing the election were sent on July 6 to those working and living outside the village. Villagers were invited to nominate candidates or register if they themselves were interested in running for the Qiuban VC, which would consist of one chair and two ordinary members. We were told the Qiuban Party Secretary was encouraged to run for VC. Mr. Wang did not put himself up as a candidate. There were three self-nominations. By July 15, there were four candidates for the chair and four for the VC membership. Two candidates dropped out on July 14 and 18, respectively. A second VRA meeting was held on July 24 and adopted a series of resolutions including postponing the election to August 2 (for the Center to observe), approving election workers nominated by VSGs and deciding how to determine a voter's intent if wrong characters were written on to the ballot.(28) 4. Candidates’ Forum. A meeting of the VRA to introduce and question those who declared their candidacy was held on July 25 at the local school. A lottery was offered to the candidates as to who would speak first at the Q & A session. The meeting began at 8:00 pm and did not end until almost midnight. After each campaign speech, villagers took turns questioning them. Some of the questions were quite sharp.(29) For example, after Lin Nongye, a storeowner running for the VC chair spoke, he was peppered with questions on how to increase the village’s agricultural income, how to expand agricultural products processing and what to do to introduce more village enterprises. After Wang Chengtuo, who owns a minibus business that takes villagers to the county city, outlined his blueprint for the village, he was asked how he could fulfill his responsibility as a village chair if he spent most of his time driving the minibus. One villager confronted him on how to solve the infighting problem in the village and promote unity and consensus. The villagers also quizzed candidates on how to take care of the elderly and offer a better education to a young generation. Election Observation The haixuan election was set for August 2 from 8-11:00 am, at the Qiuban Village school compound that had been decorated with colored balloons and red banners to create a festive atmosphere. Three ballot stations, one per VSG in the village, were set up, each with a secret ballot booth. Scribes to write out ballots for those who are illiterate and other election workers were recruited from other elementary schools outside the village. Roving ballot boxes were organized for three voters who were confirmed as having trouble physically coming to the polls. Proxy forms for those living outside the village were collected and registered. Officials from other townships and peasants from nearby villages showed up to watch the proceedings. Residents gathered in the courtyard to hear instructions from the VEC members, who were seated in front of the gathering. Ballot stations had been set up according to the three VSGs, with rope strung to make for orderly lines at each station. Desks were set up first to check voters’ voter identification cards against the master voter registration list and proxy authorization forms against the proxy list. Voters then proceeded to get their ballot and waited to enter the secret ballot booths. Each consisted of a curtained-off desk and chair set up in a classroom. Each room also had a curtained desk for use by the scribe when necessary. The election workers appeared to do a thorough job of checking voter cards and proxies against registration lists, stamping the cards, issuing ballots and ensuring that only one person entered each booth at a time. However, the ballot writing took a long time, as the names had to be handwritten on the blank ballots. While the voting was in process, Chuck Costello, Director of the Democracy Program at the Center and head of the delegation, questioned a villager who attended the candidates' forum and asked two questions. Mr. Wang, 57 years old and a plum farmer with an annual income of 7-10,000 yuan depending on the harvest, reported the forum had lasted until nearly midnight and was very lively, with about 300 villagers in attendance. His two questions for the candidates were (1) how to develop the agricultural economy, and (2) how to develop collective enterprises. He said he was satisfied with the candidates' answers, but questioned whether they could actually fulfill their promises. He said everyone was excited about the meeting, and that he had not made up his mind before the meeting as to for whom to vote but would vote for those who had answered best. This was the first time Qiuban had held such a candidates' forum. Another elderly couple was questioned and also said they had found the forum to be very helpful. The man said he thought the former VC chair was satisfactory, as he had increased the income of the village and built the school in which the election was being held (although we had heard he was not standing for re-election due to widespread dissatisfaction). A third man questioned, had attended the forum for almost four hours, and said it had helped him make up his mind for whom to vote. The man said he would vote for those he thought were the most selfless. Voting was finished pretty much on time, shortly after 11:00 am. The ballot boxes were arranged in a row on tables set in front of a divided-off area of the courtyard, to keep the crowds back yet allow them to watch the proceedings. Ballot boxes were unlocked and opened. Ballots were emptied onto large round baskets and then counted. Roving ballot boxes had been prepared for three voters, but two of the three showed up in person to vote. Three election workers had accompanied the boxes. The single ballot from the roving ballot box was mixed in with the others after the initial counting. 419 ballots were issued and returned, including 64 proxies, and all were valid, thus achieving the 50% threshold of voter participation required by the Organic Law and the Measures to validate the elections. The turnout rate was at 94% (419 out of 444). We were told that the VRA would decide if a ballot was valid in the event of any controversy or doubt raised by the VEC. Local rules make clear such things as mistakes in writing out the names, for example, should not invalidate the ballot. The ballots were first counted by election workers assigned to each VSG to ensure the number of ballots cast did not exceed that of registered voters. The ballots were then mixed together and redistributed to the ballot counters, so that it would be impossible to determine how each VSG had voted. Ballots were then checked to make sure they were legible and valid, and the total number of ballots cast was announced. The ballots were then called out and the votes recorded on two blackboards, with the results announced on the spot. The top vote getters were:

Since no one candidate garnered over 50% of the total ballots cast, another election was scheduled for August 5. This election was to be treated as a general election (again requiring that candidates receive over 50% of ballots cast in order to be elected) rather than a run-off election (in which only 1/3 of ballots cast is required for election under the prior rules, which were being applied to the Qiuban elections rather than the new Electoral Measures adopted July 28, which call for a simple majority in a run-off election), with the haixuan process thus having served as a primary election. A few days later, an election was held in Qiuban with two candidates for the chair and three candidates for the member positions. 303 ballots were cast, indicating a much lower turnout rate at 68%. Lin Nongye won and became the chair with 278 votes. Huang Liantong and Wang Zizhong won the membership race with 234 and 203 votes respectively.(31) Of the 303 ballots cast, there were 54 proxies from villagers unable to return, 9 abstention ballots and 17 invalid ballots.(32) Xiangling Village Election, August 3, 2000 Xiangling Village is a big village with 5,065 residents in 1,206 households, of which 3,425 were registered voters. We are able to reconstruct Xiangling’s pre-election activities from the public notices posted at each polling station and from conversations with villagers. A seven-member VEC with three alternates was formed through a two-step process: joint nomination by the village Party Branch and the VC and confirmation by the VRA. The first public notice, posted on June 25, informed the villagers of the makeup of the VEC. The Election Day, determined to be July 27, was made public on June 27. On June 30, the third notice conveyed to the villagers that the voter registration day was July 2 and that all villagers who left the village before this date would be considered as absentee voters and have to designate proxies. The voter registration list was published on July 7 and all complaints should be filed with the VEC before July 17. Over 100 voters were outside the village (waichu), but they were allowed to authorize proxies in writing.(33) The VEC also announced on July 7 the makeup of the VC with one chair, one vice chair and two members and designated the time from July 8 through July 11 as the nomination period. Voters could nominate candidates individually or jointly with others in their own VSGs. During this period, nomination forms were distributed to all households with instructions to return them within a fixed time. 56 nomination forms had been turned in, and then a primary to elect the official candidates was held by 48 members of the VRA, voting by secret ballots in secret ballot booths.(34) Voter registration had begun July 2, and the voter registration list posted July 7, with any comments requested by July 13. On July 12, 28 new heads of the VSGs and 64 VRA members were selected and made public. On the same day, the official slate of candidates was presented to the village with two candidates for the chair,(35) two candidates for the vice chair and three candidates for the members. On July 20, another notice declared that all the candidates had passed eligibility checks by the town and county governments as well as the VEC.(36) Finally, Election Day details and a list of those voting by roving ballot box were posted. We were told that Xiangling also held a candidates' forum in the form of a VRA meeting that was open to everyone. There was not much time for us to find out more details of the forum but we did see campaign speeches by the two candidates for the chair posted at every polling station. The speech of Chen Guoxing, the incumbent, and number two in the Party, was full of past accomplishments and grandiose projects for the next three years if reelected. He wanted voters to know that in the past three years he raised the average income per capita of the villagers from 1,850 yuan to 3,450 yuan and that he installed FR radio in the village, brought tap water to most of the homes and built a cement road. He promised that he would resign if he could not get the village road widened in the next three years and he would try to raise the annual per capita income to 4,000 yuan. He also vowed to build a dormitory building for village schoolteachers and install cable television and optical phone lines to each household. In contrast, the speech of his challenger, an enlisted PLA soldier until 1999, sounded empty and hollow with no past achievements to boast of and no future blueprint to offer. Election Observation Polling stations were established in temples, ancestral halls, schools, and private homes throughout the widely dispersed village. A general meeting took place at 5:00 am at the central voting site, located where the government offices are housed, and voting took place at the various polling stations between 5:30 - 10:30 am. The roving ballot boxes were dispensed between 10:30 and 12:00, limited to those voters who were confirmed to be elderly, infirm, disabled or otherwise incapable of personally coming to a polling station to cast ballots. We first visited Polling Station #4, located in an ancestral temple. Sample ballots and color photos of official candidates for each position were posted on the temple walls. Xiangling used three ballots of different colors, one for each of the three positions of VC chair, vice chair and member. Use of the photos and color-coded ballots helped the villagers tell candidates apart, for ease of identification and filling out the ballots without need by illiterate voters for a scribe. All election-related notices, plus a color poster on VC responsibilities, were also posted. A similar set-up was encountered at Polling Station #9, located in a small temple, and Polling Station #1 at the central voting site. Voters went through the same voter ID check and ballot-issuing procedures witnessed the day before in Qiuban. Since the village had undergone a primary, the ballots already contained the printed names of the official candidates, plus an area in which the names of write-in candidates could be written. Otherwise, voters were able to use a chop provided to them in the ballot booth (a pen was also provided for any write-ins), which consisted, at Polling Station #4, of a desk set in a room off the altar area, viewable from both the altar area and the area in front of the altar. Although only one desk was set up in a room (ballot booth), it was not curtained off, so the person could be watched while writing out the ballots. All ballots were collected and taken to the central polling station after 12:00 noon to be counted publicly there. We did not witness this process or the counting and announcement of results, which were conveyed to us at a later meeting. The final tally was that 3,181 ballots were cast, constituting 92.7% of the voters. Apparently, all were deemed valid. The election successfully elected the entire new VC. The votes were:

Liuxian Village Election, August 3, 2000 The second village in Xianyou County that we observed was Liuxian, a smaller village with 3,144 residents in 903 households, of which 2,184 were registered voters, with 169 living outside the village (waichu). Liuxian has 45 Party members. The voters were divided among nine polling stations and were electing a three-member VC consisting of a chair, a vice chair and one ordinary member. The village has 17 VSGs and 45 VRA representatives. The average per capita income was 3,010 yuan. We obtained a glimpse of the pre-election procedures through looking at the public notices that were reposted due to our observation.(37) The first step was to form the VEC, which was made public on June 26. The VEC was made up of a chair, a vice chair, five members and three alternates. The Party Secretary and incumbent VC chair, Wang Shunqing, was the chair. Two current members of the VC were also members of the VEC. All three resigned from the VEC when they became official candidates, as required by the Measures. The Election Day was scheduled to be July 28, 2000, later changed to August 3 in a public notice to accommodate the Center's observation. 37 villagers were allowed to cast ballots in the roving ballot box. The voter registration was July 3 and the registration list was published on July 7. Notice #5 announced the makeup of the new VC as one chair, one vice chair and one member. We are not sure how the initial nomination was made by villagers but we found out in Public Notice #6 dated July 12 that six villagers were nominated for the chair, twelve for the vice chair and ten for the members. Four days later, Public Notice #7 declared that through eligibility review by the county and township Village Election Guiding Groups, the number of candidates for each position was cut down to 6, 4, and 5, respectively. No specific reason was given for the drastic candidates’ reduction. On July 17, villagers were notified that a primary to determine the official VC candidates would be held on July 20 at the Village Office courtyard and all VRA members should participate. Reportedly about 300 villagers attended the primary. The delegation did not have time to find out all the details of the primary but the confirmation of the official candidates did not appear in public until July 31 with two candidates for each position. Of the candidates for chair, Wang Shunqing, the incumbent, was elected the village Party secretary in May 2000.(38) Born in 1950, Wang had been a farmer, teacher, Communist Youth branch secretary, public safety worker, and construction worker. He divided his goals into two categories, the immediate plan, and the future agenda. The former was to introduce a village charter, enforce fiscal transparency and build an elementary school and the VC office, and the latter was to increase urbanization of the village through fruit, animal husbandry and mushroom growing, attract outside investment and eliminate corruption. Despite Wang’s incumbency and his ambitious blueprint, the 30-year old Chen Guangyang launched a credible challenge. Chen is an entrepreneur running the village quarry. He is a PLA veteran and a Party member with a middle school education. He offered a four-point plan to serve the village if elected: to enhance unity in the village leadership, to initiate daily, monthly and annual audits of village finance, to beautify the village landscape and to build a village elementary school. Observing the Election We first visited Polling Station #9, organized in a village temple, where we watched the voting process and inspected arrangements for a while, then proceeded to the central polling station, in a two-story office building, while the voting was in progress. At this station, election workers had desks outside a large room, where two curtained ballot booths were set up, one at either end of the room. In this election, we witnessed voters conferring in the ballot rooms, although election workers told us that may have been a voter conferring with a designated scribe (the scribes' desks were established outside the ballot rooms but the scribes would go into the ballot booth with the voter). However, one of our members also saw people running between the two curtained booths to confer. We stayed there until all polling stations closed and the election moved to the next stage. All ballot boxes and roving ballot boxes were brought to the central polling station. The three differently colored ballots were then separated into different piles by polling stations and counted, to determine first the total number of those voting. The count was 2,145 out of 2,184 voters, thus achieving a 98% voter turnout. The ballots were then mixed up to preserve the secrecy of the votes and divided into three piles, each containing ballots of one color (each VC position was represented by one color) for counting. The results were recorded on blackboards set up in front of the assembled villagers out in the courtyard. After the results were announced, the winners, each of whom had won more than 50% of the ballots cast, were awarded work certificates certifying their respective VC positions.

Scoring Fujian's Village Elections Fujian is known for its advanced state of village democracy and what we witnessed bears that out. The new Fujian Measures under the 1998 Organic Law are excellent and represent progress in further democratization. We are very much impressed by the straightforwardness and open-mindedness of the Fujian election officials. They are rapid in responding to new issues arising from the countryside, quick to point out existing problems in village election and willing to discuss openly all issues and questions with both domestic and Western observers. At one of the many meetings we had with the Fujian officials, Dr. John Aldrich, on behalf of the delegation, talked about the benchmarks to measure the quality of any elections. He outlined three criteria by which elections, in general, are to be judged. These are the competitiveness of the contest, the degree to which voters are informed about the contestants and the complementary degree to which candidates can be informed about the beliefs and values of the electorate, and the degree to which the sanctity of the secret vote is maintained. Collectively, these three criteria culminate in the possibility that every voter has the ability to reach his or her own informed, best choice about which candidate will best serve his or her interests. He then applied these three criteria to the village elections observed by the delegation. Competitiveness: This criterion is measured by the degree of openness of the system, that is, by how open the system is to the widest array of candidates and how open the contest is to alternative candidates winning based solely on the strength of their candidacies. (Under pressure) Aldrich graded the elections observed as an A. The “sea-election” procedure provides the opportunity for all voters to choose their most preferred candidate. In the first village observed, the system for determining which candidates were running (nomination at a central location, followed by the agreement of the candidate‘s interest in serving, if elected, followed by candidate presentations) was also a strong system on this dimension. Given that, in the first village, no candidate was able to secure a majority in the first round, the second aspect of competitiveness seemed assured there. In the third village, the chair and vice-chair incumbents won re-election easily, but the (single) member was characterized as an “upset.” Thus, it appeared that the elections were open to a variety of candidates. Informed-ness: Aldrich graded this as a B+. In the first village (Qiuban), we watched a video of a candidate forum held open to villagers several days before the election. On questioning, villagers reported that about 300 or so attended the meeting, and that it lasted either 4 or 5 hours. In the other two villages, candidates presented a written statement that was posted in public, including at the voting stations. The ability of villagers to question the candidates was unclear, likely absent although villager representatives seemed to have the opportunity to question candidates at the primary. Secrecy: Aldrich graded this as an A-. In many respects, the notion of a secret vote was observed, but we did observe technical violations and perhaps a bit of laxness in enforcing the requirements of the secret vote. The following observations include the delegation’s general evaluation of village elections in Fujian and particular assessment of the three elections it witnessed in Dehua and Xianyou:

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|